Over the last ten weeks we've been studying how well the Olympics is working for the brands that sponsor it. We're using our own social media framework to assess whether the Olympics are beneficial to the brands, taking a close look at Adidas and Cadbury specifically, and also the broader conversation about Olympic sponsorship on the whole. The last two weeks suggest that Olympic sponsorship is of most benefit to brands that are able to harness the Olympics for the greater good, making sponsorship less about selling products and more about pushing an ethos.

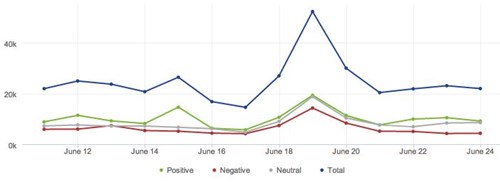

As the Olympics draw nearer, conversation about brand sponsors is picking up. The last two weeks saw around 63,000 online mentions of Olympic sponsors, compared to 54,000 the two weeks prior. The discussion points to mounting pressure on brands to make the most of their Olympic sponsorship while it lasts. This is no doubt true for our two brands in focus: Adidas and Cadbury. But the story holds a few surprises.

Adidas should have it easy. Having collaborated with Stella McCartney to create the Team GB kit, its link with the Olympics should be obvious, and with Stella and leading athletes backing its wares, you'd think this would be sufficient to give Adidas a solid boost. But so far Adidas has stumbled, and these last two weeks were no different.

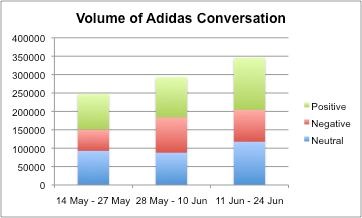

Online conversation about Adidas was up by over 30% this month, but the brand buzz was certainly not what it had hoped for.

Volume of online conversation about Adidas

Source: Brandwatch

Volume of Online Conversation About Adidas

Source: Brandwatch

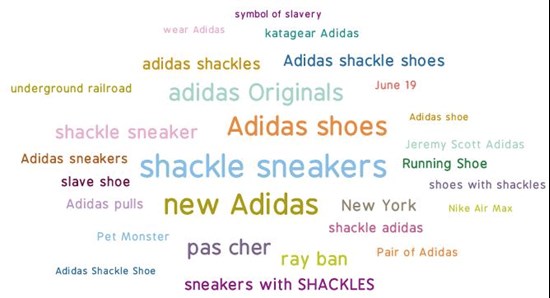

Around 19 June, Adidas saw a spike in conversation due to the release of its "shackle sneakers", a design that quickly became associated with slavery, thanks largely to discussion online and in social media.

Forbes writer John Clarke wrote, "Being a top Olympic sponsor with the London Games about one month away, Adidas' choice to hit the market with a pair of sneakers that incorporate slave shackles isn't the best idea."

Indeed, the effects were felt across social media in comments such as "'Slave shackle shoes' Adidas that's an epic fail". This can also be seen in popular terms around Adidas on the same day. (Adidas has since withdrawn the shoe.)

Source: Brandwatch

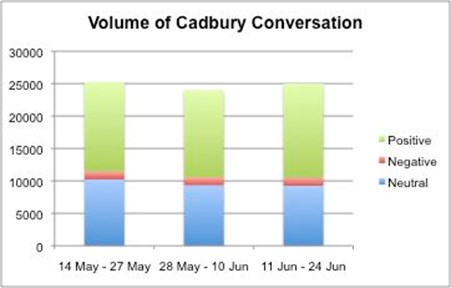

Like Adidas, Cadbury's story is also a surprise, but in the other direction. We already knew that Cadbury's not-so-healthy reputation would invite critics, and indeed they've been particularly loud these last two weeks. For example, Bad Science's Ben Goldacre, a high-profile tweeter with nearly 200,000 followers, recently posted several disapproving tweets about brand sponsors ("I honestly don't see how the people who work in a sporting association and promote McDonalds to children can sleep at night."). The comments prompted several mentions of Cadbury including "this is why I'm boycotting the whole Olympics. Sponsored by McD and Cadbury. Stupid rules about merch and the corruption."

But then you have people like Lord Coe, chair of London 2012 Olympics and an Olympic gold medalist, defending these brands, calling out the problem cases specifically: "In large part it is easy to talk fast food and soft drinks but I'm a great believer in input and output. No one is suggesting Coke and McDonald's are not doing a massive amount in terms of the legacy. They are doing an extraordinary amount to make sport come alive for young people."

Cadbury's activity suggests that there may just be some truth to this statement. In spite of its critics, Cadbury has maintained an impressive volume of positive conversation throughout this study.

Volume of online conversation about Cadbury

Source: Brandwatch

It does seem as if Cadbury has done this largely by, in the words of Lord Coe, "making sport come alive", for example, through its Spots vs. Stripes campaign, and through an ongoing series of campaigns involving consumers in Olympic-themed activities. The latest is the announcement of its plans to unveil an interactive experience, Cadbury House, in Hyde Park, to be open throughout the Games. Amongst the house's activities include a virtual race against Rebecca Adlington to win a chocolate medal. News of Cadbury House is already being well-received in Tweets such as "Oooh #Chocolate & the #Olympics - Yum! Looking forward to checking out Cadbury's Olympic House in Hyde Park".

The activities of Adidas and Cadbury suggest it's not so much the products they sell but the values they represent that matter most in Olympic sponsorship. This was highlighted in a report this week by Max Wind-Cowie of think tank Demos about measuring the social value of sponsorship, based on research with Olympic sponsor Coca-Cola.

Wind-Cowie says, "The idea that sponsoring the Olympics in and of itself is likely to encourage potential consumers to believe that you're a moral and socially valuable brand has been somewhat undone - people are less satisfied by that idea... consumers have become more savvy."

He stresses that Olympic sponsors need to tie their sponsorship with activities that benefit the greater good. Coca-Cola is doing this by, amongst other things, pledging to take all plastic waste collected at the Games and turn it into Coca-Cola bottles. Our data suggests Cadbury is doing similarly, not so much through Corporate Social Responsibility, but through the simple act of getting people to have fun, and few consumers will deny the social value in that.

About our Methodology

- Create a benchmark of Social Media chatter in English for the brands and for the topic as at 29/04/12

- Monitor changes in chatter

- Identify causes for change in levels of chatter

- Assess to what degree changes are beneficial or other wise to the brand

- Assess to what degree Social Media is driving the changes and, as a phenomenon, improving the marketing & PR process for the brands in focus and the wider story